Lin Wen Yi (Partner), Fuguan Law Firm (giana.lin@fuguanlaw.com)

Sun Yan (Attorney), Fuguan Law Firm (karen.sun@fuguanlaw.com)

Almost every article discussing impact investment mentions the origin of the term “impact investing.” It was first defined in the 2010 report Impact Investments: An Emerging Asset Class jointly released by J.P. Morgan and the Rockefeller Foundation. The report posited that, compared to traditional investing, impact investing refers to investments that actively seek positive environmental and social impacts alongside a financial return, emphasizing precise measurement of social impact, sustainability of financial returns, and mobilizing diverse actors to jointly address social problems.

While writing this article, the authors discussed with many industry insiders, each holding their own views or even convictions about what constitutes impact investing. They also expressed hope that academia and the practical field could reach a consensus on what truly qualifies as impact investing. This is because they believe many so-called impact investments merely add a veneer of impact to fundamentally financial investments. The authors explore this definition further in another article, Considerations for Institutional Investors Participating in Impact Investing.

Impact investing has become a significant pathway for corporate capital sharing both domestically and internationally in recent years. From observations of practices within China, this trend manifests in several ways:

- Concept-advocacy organizations continuously introduce concepts and explore practices based on research and practices from abroad and within China;

- A growing number of investors are becoming aware of impact investing, considering the feasibility of “combining purpose and profit,” with many making attempts at “impact investing”;

- An increasing number of investees, including organizations and entrepreneurs, are beginning to think from both ends toward a middle ground: how to integrate solutions to social problems into existing business models, and how, upon identifying a social problem to solve, to incorporate a viable business model to secure sustainable resources for addressing that problem.

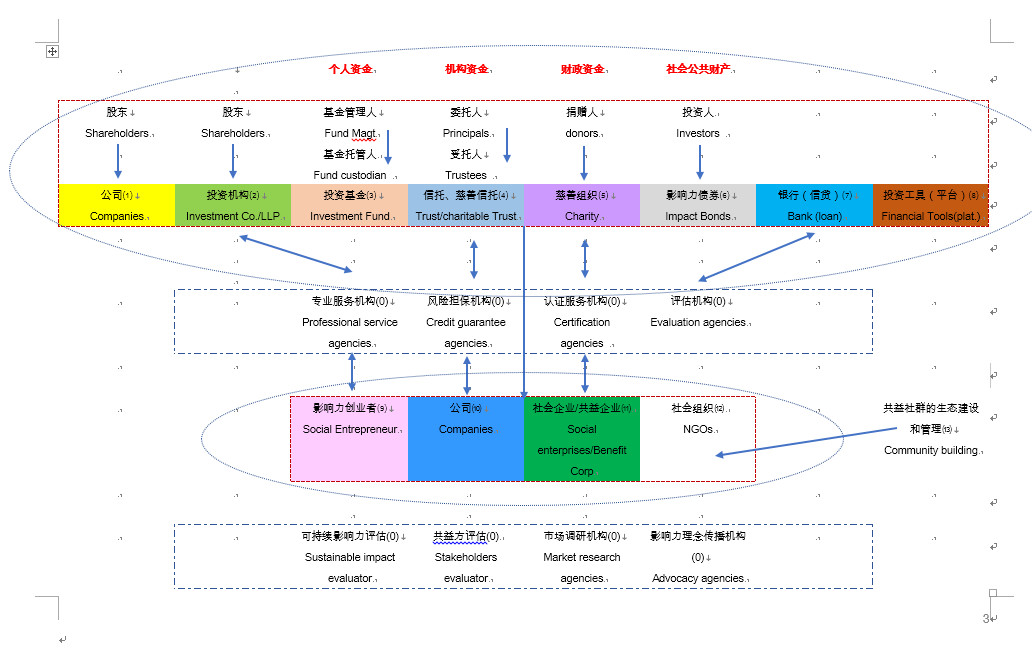

Based on research and practical experience, the authors attempt to provide a panoramic overview of the structure of impact investing in China. This panorama considers investment structures currently present in the Chinese market, structures with existing practices abroad that are legally feasible in China, and also discusses structures considered possible for impact investment in academia but which face investment barriers under current laws.

The overview primarily adopts three perspectives: first, discussing the legal relationships and applicable laws involved in various investment forms from a legal standpoint; second, examining the characteristics of the main legal entities involved in these structures; third, based on the first two, preliminarily exploring the infrastructure yet to be developed for impact investing.

**(0) Supporting Institutions:** Sustainable Impact Assessment Agencies, Benefit Corporation Assessment Agencies, Market Research Agencies, Impact Concept Dissemination Agencies, Professional Service Agencies, Risk Guarantee Agencies, Certification Service Agencies, and Post-Investment Evaluation Agencies.

**(0) Supporting Institutions:** Sustainable Impact Assessment Agencies, Benefit Corporation Assessment Agencies, Market Research Agencies, Impact Concept Dissemination Agencies, Professional Service Agencies, Risk Guarantee Agencies, Certification Service Agencies, and Post-Investment Evaluation Agencies.

(0) Supporting Institutions hold a position of primary importance because they play a pivotal role in the entire impact investing ecosystem. An investor might be moved by an investee actively concerned with environmental and social impact and decide to invest. If the investee’s business model is sufficiently effective, this could be an impact investment sample achieving both social value and financial return. However, without the involvement of (0) Supporting Institutions, this might merely be an isolated incident.

The authors believe that the development level of (0) Supporting Institutions reflects the maturity of a country’s impact investing landscape and constitutes crucial infrastructure for impact investing.

- Impact Concept Dissemination Agencies possess not only strong research and advocacy capabilities but often also the ability to connect domestic and international investment capital. They are dedicated to popularizing the concept of impact investing, making it visible, quantifiable, measurable, and providing a degree of predictability. For participants in investment activities and policymakers, they are sources of theoretical information and practical impetus.

- Impact Assessment Agencies are committed to using scientific tools for quantifiable qualitative and performance evaluation of impact. Compared to ESG investing (“ESG” stands for Environment, Social, and Governance), the qualification of what constitutes an impact investment still lacks a unified standard. Simultaneously, the quantifiability of impact investing is not as advanced as ESG investing. From a market perspective, evidence seems close to proving that performance in ESG ratings may have some positive correlation with financial returns.[1] However, for impact investing, as the financial information of invested companies is not mandatorily public (and much involves trade secrets), it is difficult to calculate, from limited samples, whether there is any degree of positive correlation between impact assessment results and financial performance in the short or long term. Under these circumstances, expanding the scale of investment from rational investors and institutions (those who prefer predicting returns through data analysis) faces certain difficulties. For impact assessment, market research, data collection, and tool development rely on the growth of specialized agencies.

- Social Enterprise Certification Agencies are closely related to certification systems. In China, the more common ones are the China Social Enterprise Certification and B Lab’s B Corp (Benefit Corporation) certification. Many believe that the legal status of social enterprises in China is an urgent issue needing resolution, a view with which the authors concur. Current certifications include those by industry associations and social organizations (NGOs), such as the Beijing Social Enterprise Development Promotion Association in Beijing and SheChuangXing in Shenzhen; internationally aligned certifications like B Corp; and local government pilots and practices, such as Chengdu’s social enterprise review and a series of support pilots. For internationally aligned certifications like B Corp, localization for China has not been fully realized. Complete compatibility between certification systems and impact assessment systems has not been established. Homogeneous parameters allowing for comparison or consolidated investment analysis between social enterprises/benefit corporations under different certification systems are lacking, making it difficult to provide integrated investment guidance for investors. This challenge requires joint resolution by the aforementioned impact assessment agencies and certification agencies.

- Professional Service Agencies, including legal, financial, and other firms specializing in serving impact investors or investees. They ensure the compliance and effectiveness of investments. Participating in impact investing as professional service providers with a comprehensive view of an investment, they can, with sufficient accumulated experience, play a bridging role in the industry. On one hand, they can relay market policy needs to policymakers; on the other, they can offer effective, compliant, and diverse investment advice to clients. For example, in Europe, Esela (eu) is a non-profit global network of lawyers, consultants, academics, and social entrepreneurs dedicated to fostering a better understanding of laws in areas that create sustainable and inclusive economies and promote positive social impact, thereby supporting the development and growth of a more sustainable and inclusive economy. Our firm actively participates in the network building and exchange activities of Esela’s Asia-Pacific region.

(1) Companies (as investor companies) and (2) Investment Institutions

(1) and (2) are legally similar in structure. As investing entities, their registered forms are mostly limited liability companies (with (2) also commonly taking the form of limited partnerships), investing in investees through equity investment. The distinction is that (2) Investment Institutions have equity investment as their business scope, especially under the limited partnership form, allowing them to pool funds from numerous limited partners for larger-scale investment activities.

(3) Investment Funds

(3) primarily refers to privately offered funds, specifically private equity funds. (3) may be the product of the scaled development of (2). Privately offered funds are generally custodied by fund custodians and managed by fund managers. In current Chinese impact investing practice, investment funds often take the form of venture capital, angel investment, or leveraged buyouts. Current domestic impact investment targets are all unlisted companies. The operational model of investment funds shows no substantive difference in investment structure from non-impact investing. Obtaining dividends from investees is not the primary profit method for investment funds; profit comes from equity transfers after the investee goes public or secures further financing. This is based on the expectation that investees, after receiving fund investment, can achieve leapfrog development and exponential valuation growth. For example, Shenzhen Liandi Information Accessibility Co., Ltd., invested in by the Manna Impact Investment Fund, experienced 18-fold growth within four years post-investment.

From the perspective of current laws regulating the investment behavior of (1), (2), and (3), all three investor types can execute investments into target entities. However, whether such investments can be termed “impact investments” likely requires consideration of more factors, such as:

- The first consideration is balancing shareholder rights protection with the achievement of social objectives. For companies receiving impact investment, due to their mission, they must either effectively integrate solutions to social problems into their business model or add a business model to a problem-solving process. Both approaches may create conflicts or force trade-offs for the investee’s management between maximizing shareholder profit and fulfilling the social mission.

Investor-shareholders typically do not engage in daily operations, delegating management to professional managers. When managers formulate business plans, budgets, final accounts, and profit distribution schemes, how to balance the aforementioned conflict without being deemed as harming the company or shareholder interests is a key consideration. Taking a specific impact investment as an example, its primary social objective is reducing operational costs for a certain low-income worker group. Managers could achieve cost reductions for beneficiaries ranging from 50% to 80%, with the company’s distributable profits fluctuating accordingly. Clearly, if management opts for the maximum cost reduction (maximizing social impact), distributable profits would be minimized (though not eliminated). In such cases, the authors believe the company’s articles of association should include protective provisions for this bidirectional balance, shielding managers from shareholder lawsuits for decisions pursuing social goals while ensuring shareholders still receive a financial return. Similar considerations apply to fund advisor regulations, needing stipulation in fund contracts.

- The second consideration is the investment cycle. Few impact investees have mature business models and optimal solutions for a social problem. Most are likely in the startup phase, some not even incorporated—perhaps as a business entity undergoing transformation or a non-profit seeking sustainable development via a business model. Whether establishing or transforming the legal entity or pivoting the business model, time is required, significantly affecting the investor’s capital return cycle, necessitating stipulations in the articles of association or fund contracts.

- The third consideration is the investment evaluation system. This is among the most crucial pieces of infrastructure for impact investing, comprising a localized, effective evaluation system and professional agencies to implement it. As mentioned, an investee in the early stages may not provide sufficient financial data for professional investment judgment. Based on observations, current impact investors primarily use three decision-making methods: traditional financial investment evaluation; internationally common impact evaluation systems like GIIN’s IRIS+[2]; or evaluation systems developed by investors combining China’s context with their own preferences, such as the Manna Impact Investment social value objectives or the “3A-3L” social value investment criteria.

An effective evaluation system for impact investing should not only measure social value indicators but also align with traditional financial metrics, even establishing linkages between them to facilitate investor decision-making. However, this requires a sufficient base of impact investment cases and data statistics. Unlike ESG investing research (where quantifiability is currently far superior), most current impact assessment standards focus on quantifiable impact measurement and analysis, paying less attention to financial metrics, especially the overall return performance of impact investments. This remains an area requiring more persuasive evidence for investors seeking to scale impact investment capital.

(4) Trusts (Including Charitable Trusts)

Trust company plans can be layered within (3), act as Limited Partners (LPs) injecting capital into investment funds, or directly issue private equity fund products. The feasible options within (4) remain traditional trust companies and trust plan products, as under the existing legal framework, they can directly invest in investees, delegate to professional impact investment management advisors, or act as LPs injecting capital into investment funds managed by fund managers.

It is worth mentioning that domestic academic research on impact investing notes the potential for charitable trusts to participate.[3] Charitable trusts fall under public welfare trusts. Whether under the Charity Law or the Trust Law, legal obstacles currently exist for public welfare/charitable trusts engaging in impact investing. The purpose of a public welfare trust must align with legally defined public interests, and activities of a charitable trust are limited to charitable activities defined by the Charity Law. Since impact investees can only be for-profit business entities, not social organizations (NGOs) (see discussion on (12) below), this would require the invested entity’s public interest (social value) to completely outweigh private interests (shareholder equity), which is nearly impossible in practice. For example, investing in a tech startup dedicated to green takeout packaging could be argued to serve environmental or technological causes. However, as private parties also benefit, whether such an investment via a public welfare/charitable trust violates the public welfare principle and its compliance remains highly challenged.

(5) Charitable Organizations

In China, investment activities by charitable organizations have always been strictly regulated, with a general lack of support from personnel or agencies with professional capability. The Interim Measures for the Management of Value Preservation and Appreciation Investment Activities by Charitable Organizations, in whose drafting the authors’ organization ForNGO participated and which took effect in 2019, permits charitable organizations certain investment activities, including:

- Direct purchase of asset management products issued by financial institutions such as banks, trusts, securities, funds, futures, insurance asset management institutions, and financial asset investment companies;

- Direct equity investments related to their business scope through initiation, acquisition, or share participation;

- Entrusting assets to institutions supervised by financial regulatory authorities for investment.

However, in practice, whether charitable organizations, especially those with public fundraising qualifications, can use impact investing as a charitable activity for fundraising faces difficulties similar to those described for charitable trusts. Although charitable organizations can use non-restricted assets and temporarily undisbursed restricted assets to purchase asset management products under (3) and (4), indirectly participating in impact investing, such operations, without public fundraising, are hard to scale and differ little from purchasing other asset management products.

(6) Social Impact Bonds

As an innovative financial model, Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) have unique advantages and operational methods. Consequently, some countries with faster SIB development have enacted corresponding laws, such as the U.S. Senate’s 2015 Social Impact Partnership Act, the UK’s 2014 Social Investment Tax Relief, and Canada’s 2012 Economic Action Plan 2012. In China, where the legal status of SIBs is not yet clarified, current “social effect bond” issuance practices apply the Administrative Measures for Debt Financing Instruments of Non-Financial Enterprises in the Interbank Bond Market and related rules, incorporating them into the interbank bond market management system. Under this structure, an issuer-investor debtor-creditor relationship is formed.

The core of SIBs is public-private partnership, where governments use private investment to cover upfront social service costs, fund high-quality services through performance contracts, and collaborate with high-level service providers.[4] The internationally prevalent SIB model differs significantly in legal structure from China’s social effect bonds. The former are not bonds in the substantive sense but resemble a series of “pay-for-success” contingent contract arrangements; the latter are statutory bonds. China’s social effect bonds only incorporate social benefit indicators in the evaluation phase as a reference for interest rate adjustments but remain essentially traditional principal-plus-interest models.

In fact, the inception of SIBs in the UK had a specific social context: a “triple failure” in social services by government, market, and non-profits, strained government finances making large investments in early prevention/intervention projects difficult despite their economic and social benefits, non-profits facing long-term funding shortages hindering scale, and interested investors lacking objectively assessable investment targets. Thus, SIBs emerged as a new contractual financing method linking social service payments to measurable outcomes, aiming to transfer government risk via social capital while providing high-quality, effective services. In China, the current state of social services differs markedly from this context. The “big government, small society” pattern persists, with limited government willingness to transfer fiscal risk via social capital. Service purchase recipients are often Chinese social organizations. Given their overall early development stage and the weak empirical research base for assessing project impact, attracting return-focused private investors is challenging. Therefore, while individual social effect bond cases in China borrow some SIB concepts, whether they represent true “Social Impact Bonds” as understood internationally or merely a diversification of traditional bond evaluation metrics is highly questionable. In other words, whether SIB design objectives suit China’s current socio-legal environment and achieve expected effects requires further research and discussion on all aspects, including involved entities, operational norms, and assessment infrastructure.

(7) Banks (Credit)

As a traditional economic activity, bank loans are heavily influenced by policy guidance and restrictions. Their role in driving innovation within impact investing is relatively limited. Primary participation forms include providing leveraged buyout funding sources for other impact investors.

Compared to mezzanine capital from mezzanine funds, insurance companies, or public markets, bank loans offer lower financing costs but correspondingly lower flexibility. In a pure impact investment, with long return cycles and less measurable, comparable returns, raising funds from return-seeking institutional or individual investors may be difficult. In the early stages, bank loans can provide low-cost, high-priority investment assets for impact investors. After establishing a performance track record, fundraising can shift to financial investors. From this perspective, if bank credit policies could respond to this market demand, facilitating early-stage financing for impact investors, it might significantly promote impact investing success. Besides lending to investors, banks can directly lend to investees, e.g., venture loans. In practice, venture loan amounts are generally low, often considering borrower resources, repayment capacity, or requiring collateral. Venture loans typically have term limits, being term loans, which may not align with the patient capital return cycles of impact investing. If bank credit products could incorporate impact investing characteristics into venture loans, they might become a preferred option for investees unwilling to exchange equity for investment.

From the bank’s perspective, for impact venture loans, beyond standard credit considerations, the aforementioned impact assessment tools should be introduced. Investees passing such assessments would benefit from more favorable credit terms.

(8) Investment Tools (Platforms)

Investment Tools (Platforms) refer to market-innovative financing platforms and investment tools outside the aforementioned categories. They sometimes use internet technology, but currently, they mostly exist based on contractual relationships and often carry certain compliance risks during fundraising.

(9) Impact Entrepreneurs (Social Entrepreneurs)

Limiting impact investing to existing companies would miss many excellent impact entrepreneurs. Their perspectives are often valuable, coupled with practical ability. Providing early-stage funding to such entrepreneurs is called impact venture investing.

Current national policies supporting venture investment[5] aim to integrate technology, capital, talent, management, and other innovative elements with startups, forming a capital force promoting mass entrepreneurship and innovation, facilitating sci-tech achievement conversion, advancing supply-side structural reform, fostering new growth drivers, stabilizing growth, and expanding employment. While these policies may support some impact entrepreneurs, they are not fully applicable. Impact entrepreneurs focused on non-policy-led social issues may still not benefit.

Without state support, discovering and funding these entrepreneurs through social capital becomes particularly important. Many impact investors use their channels to identify and invest in impact entrepreneurs, and many entrepreneurs hope to gain visibility to achieve their goals.

Searching the Asset Management Association of China with “impact” as a keyword among fund products yields only one venture capital fund: Shenzhen Feifan Shulian Impact Venture Capital Partnership (Limited Partnership)[6], filed by Shenzhen Feifan Shulian Equity Investment Management Partnership (Limited Partnership). According to searches, Feifan Shulian was established on the Digital China platform, focusing on early-stage investment and nurturing “three-have” entrepreneurs (having dreams, capability, and social responsibility) as a new type of impact venture capital. It is jointly invested by the Shenzhen Angel Mother Fund, Futian Guidance Fund, and Tencent Industrial Fund.[7]

Beyond private investment, we anticipate the government will enhance the identification, recognition, and corresponding support policies for impact entrepreneurs.

It is worth mentioning that some scholars advocate for “public welfare capital” entering early-stage projects for impact investment[8], followed by venture capital co-investment. The authors hold a different view. While the article does not define “public welfare capital,” it generally includes assets of social organizations. This differs fundamentally in nature from venture capital and equity capital. Under the Civil Code, venture and equity capital constitute private property rights, whereas assets of social organizations, per the Public Welfare Donations Law, belong to social public property. Social public property should be used for public welfare causes, avoiding losses. The spirit of the aforementioned Interim Measures also emphasizes risk control as a principle for charitable organization investments. Therefore, laws, regulators, and public opinion are very cautious about losses to social organization assets from investments. For venture and equity capital, their purpose is investment for return, accepting corresponding risks. Thus, for impact venture investing, lead investment by institutional investors coupled with state policy support is the more ideal scenario.

(10) Companies (as investee companies)

Companies include certified social enterprises/benefit corporations, and companies integrating social responsibility or value into their operations.

Limiting impact investing to social enterprises/benefit corporations would overlook the latter’s social value contributions. However, whether investment in the latter qualifies as impact investing requires verification through impact assessment tools. In short, given the unclear legal status and supporting policies for social enterprises in China, whether investing in a company constitutes impact investing depends on the company passing a valid impact assessment. Without such assessment, the investment cannot serve as a research sample for impact investing, lest it affect data analysis validity.

(11) Social Enterprises / Benefit Corporations

Some argue for a narrow definition: only investments in social enterprises/benefit corporations qualify as impact investing, as their characteristic is addressing social problems through business models, aligning best with impact investing requirements.

Just as non-profits cannot engage in for-profit operations, the nature of social enterprises/benefit corporations ensures investment inherently generates social impact. However, even if investing in such an entity is termed impact investing, investors must also consider financial returns to avoid missing a crucial factor.

(12) Social Organizations

A significant legal misconception in some domestic academic articles is the notion of investing in social organizations, even suggesting lifting legal restrictions on their profitability.[9] The misunderstanding lies here: social organizations include foundations, social groups, and social service agencies. Post-revision of the Private Education Promotion Law, all three are non-profit legal persons under the Civil Code, subject to the non-profit principle prohibiting profit distribution. Founders, contributors, or members cannot receive profit distributions from social organizations, fundamentally negating their ability to pay investment returns.

Furthermore, assets of social organizations are social public property, lacking the concept of investor equity. Thus, investing in social organizations is currently legally infeasible.

The issue of social organization profitability is separate, referring to their ability to engage in profit-generating activities within their charter and scope, distinct from being profit-oriented (seeking returns). Therefore, there is no need to “lift restrictions” as none exist; current law prohibits profit distribution.

In practice, social organizations as impact investees typically involve adding a business model to a social value focus (all have a public welfare mission). This often requires registering a new for-profit entity—a legal transformation into an investment-receivable business entity. Some cases involve social organizations co-investing with others to establish such entities. However, as mentioned in (5), this carries compliance risks, strict supervision, and controversy.

(13) Benefit Community Ecosystem Building and Management

In the panorama, this represents interaction between impact investors and investees, possibly led by investors or (0) Supporting Institutions. Currently, such community forms are rarely large-scale in China, but their importance is undeniable.

In an interview with Manna Impact Fund, they distinguished passive returns as β value. The fund identifies entities with β value by focusing on the “technologically abandoned,” investing in them. Through subsequent incubation tools and what they term “value management,” they foster value growth, creating new value termed α value—new projects or value generated via incubation. Community operations, through developing and applying financial or incubation tools, find linkages with social value, proactively managing investments to generate new projects, thus achieving +α composite returns.

Conclusion

This article attempts to outline a panoramic overview of participants and infrastructure in China’s impact investing, enabling readers to understand at a glance the various participants, feasibility of investment forms, and infrastructure needing development (including participant growth, industry policy, and tools). Some impact investing research articles express expectations for investments in specific social sectors, which are not this article’s focus.

Based on the above overview, the authors’ forward-looking perspectives on China’s impact investing are as follows:

First, from an industry infrastructure development perspective:

- Hope for more **(0) Supporting Institutions** participating in China’s impact investing ecosystem;

- Based on the above, moving towards a more unified impact assessment standard. This system should enable quantifiable, comparable analysis of different impact investment performances while reflecting relationships between impact and financial returns;

- Promoting information disclosure among investees, enabling social supervision and providing market research agencies sufficient samples for developing impact investing tools.

Second, from a participant and investment form perspective:

- Deeper research, including policy research, is needed for potential capital providers like charitable trusts, social organizations (including charitable ones), or impact bonds.

- Regarding participants, more focus is needed on effectively discovering impact entrepreneurs, exploring achievable social value within existing business models, and developing sustainable business models based on existing social value creation.

Finally, from a policy perspective:

- Policy should provide identification for impact investing, impact investors, and impact entrepreneurs;

- Actively consider legislation or promoting local social enterprise certification and impact investment support policies;

- Based on impact investing identification, offer lower-cost, more flexible credit support in credit policies;

- From a regulatory standpoint, promote industry self-regulation, encourage information disclosure, and foster a comparable, analyzable, freely competitive impact investment market environment.

[1] On October 24, 2019, China Securities Index Co., Ltd. announced the launch of the “CSI Sustainable Development 100 Index”; on November 15, the “CSI Sustainable Development 100 Index,” with data provided by Social Value Investment Alliance (Shenzhen) and customized by Bosera Fund, was listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange. From June 30, 2014, to September 30, 2020, the total return of the CSI Sustainable Development 100 Total Return Index was 167.34%, outperforming the CSI 300 Total Return Index by 24.30 percentage points; the annualized return was 17.46%, 1.82 percentage points higher than the CSI 300 Total Return Index. (Data source: *2020 A-Share Listed Company Sustainable Development Value Assessment Report – Discovering China’s “Purpose-Profit 99″*, Social Value Investment Alliance, Editors: Ma Weihua, Song Zhiping)

[2] Products providing investors with core metric sets by investment theme and/or linked to Sustainable Development Goals, evidence-backed, and supported by practical guidance.

[3] “Research on Financing Models for Social Impact Investment Based on Structured Contract Design”, China Price, 2020.3, China Academic Journal Electronic Publishing House, P64.

[4] See Hao Zhibin, Foreign References for the Legalization of Social Impact Bonds, Securities Market Herald, June 2019.

[5] State Council Opinions on Promoting the Sustainable and Healthy Development of Venture Investment, issued by the State Council, effective September 16, 2016.

[6] Feifan Shulian is an impact fund focusing on early-stage investment, dedicated to supporting young entrepreneurs with dreams, capability, and values, achieving a balance between corporate social and commercial value creation. The management team comprises partners from top domestic funds and successful entrepreneurs, focusing on high-tech, biopharma, and new consumption sectors, aiming to connect and accompany more entrepreneurs in self-breakthrough and rapid growth.

[7] http://www.geneus-tech.com/index.php?c=article&id=108, “Genius Tech Wins Top Prize at Digital China Entrepreneurship Competition”, last accessed: January 24, 2021, 19:38.

[8] Current Status, Trends, and Recommendations for Impact Investment Development, Securities Market, Issue 9, 2020 (Total Issue 494), p88.

[9] Current Status, Trends, and Recommendations for Impact Investment Development, Securities Market, Issue 9, 2020 (Total Issue 494), p86.